What do we leave behind? Thinking beyond programme horizons in student-centred accountability

When a development programme ends, what matters most? For the supported activities to continue? For the approach to be adopted elsewhere? For participants to carry forward what they have learned, or experienced? For broader systems and attitudes to shift?

These aren't just academic questions; they're practical considerations that should shape how we design programmes, allocate resources, and measure success. And they're questions we've been re-asking ourselves as we approach the end of our latest school-based accountability initiative, which has established Integrity Clubs in ten schools of Kenya's Kilifi County through our partnership with Kesho Kenya.

We asked our evaluators to not only explore the difference that these ten new clubs are making, but to also visit some of the schools we previously established clubs in through our SHINE programme (2017-2021).

The immediate picture was sobering: all five SHINE schools we selected no longer had active clubs. We had hoped they would continue. But the discovery pushes us to return to those more fundamental questions around what we're trying to sustain, and what might endure even when formal structures fail.

What impact is there to sustain?

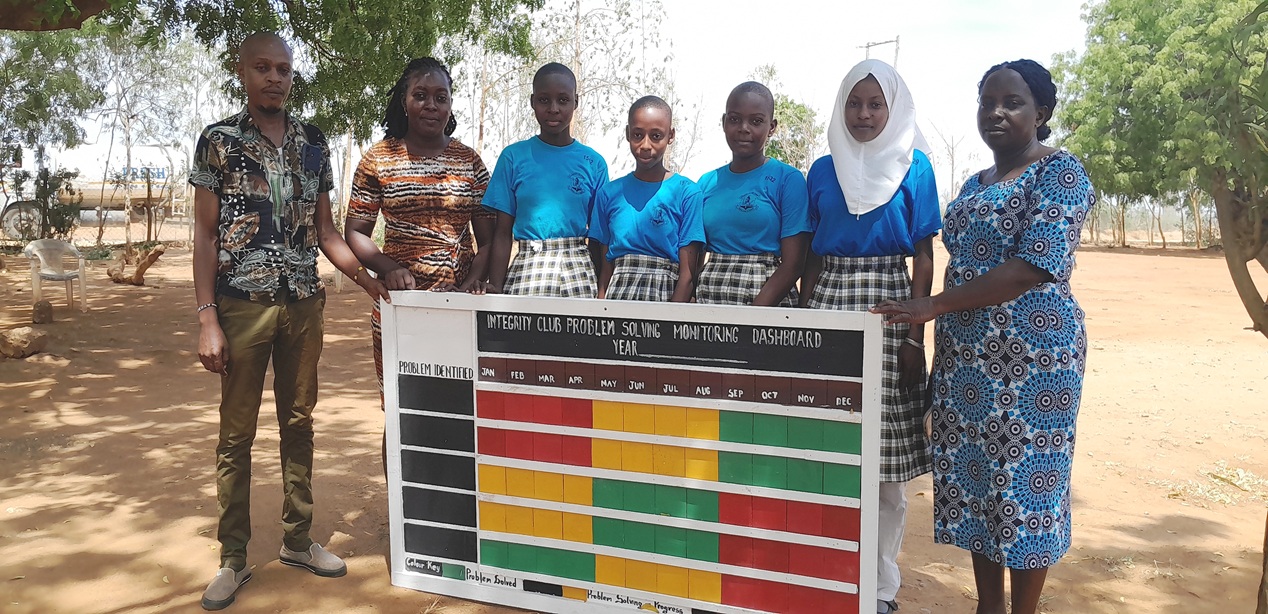

First, let's be clear about what Integrity Clubs do achieve. These are school-based, student-led groups through which teenagers aged 14-18 learn about accountability, identify issues affecting their education, and work with school management to resolve problems. As our new evaluation shows, the results have been rapid and profound.

When Integrity Club members monitor their surroundings, the school environment improves. New laboratories and toilets are built, solar panels are installed, buildings are painted, broken furniture is replaced. The environment is not only physical: one club member's request led to his school participating in county drama festivals that had previously been neglected, providing enrichment opportunities for all students. And club members don't merely report problems, they solve them collaboratively. Through constructive dialogue rather than confrontation, students have successfully addressed teacher shortages, water scarcity, poor hygiene, and inadequate sports materials.

As a result of all this problem-solving, Integrity Club members frequently describe valuable personal transformations such as improved self-confidence and leadership skills. Several cited their experience to the evaluators as a “stepping stone” to formal positions such as school prefects, or even head boys and girls. As one of them put it:

"We are now more confident, take initiative, and are even doing presentations [elsewhere], for example in the annual general meetings."

~ Integrity Club member, Fundi Issa Secondary School

The effects extend beyond the confines of the Integrity Club itself. Fellow students are described by their teachers as adopting the values of honesty, responsibility, and respect that club members model. A teacher at Galana Boys School described how "in the dorms, there was shouting and stealing at night last year. This year, it is quieter, due to peer counsellors in the Club."

Teachers themselves also become more responsive to student needs – more punctual, less likely to play favourites, actively offering additional lessons – while other school staff such as cooks and security guards have changed behaviours to the benefit of all students. One teacher at Marereni Secondary School stated that Integrity Clubs are "making us lead by example." Another said:

“I have seen drastic changes in the students. This [school] environment is hostile, where sometimes the students became rowdy. Now, I see other students respecting Club members and students even keep each other in check.”

~ Teacher, Ngomeni Secondary School

So why have clubs stopped?

The outcomes described above were also found in our previous Integrity Club programme, SHINE. Teachers in the five revisited SHINE schools validated the changes they remembered seeing. So why had those clubs stopped operating?

The new evaluation identifies clear reasons: resource constraints, teacher transfers, competing demands, and crucially, lack of institutionalisation. Schools hadn't budgeted for club activities, Boards of Management and parents weren't actively engaged, and the position of club patron was viewed as extra work for teachers rather than integral to their role.

In short, Integrity Clubs remained discrete ‘projects’ rather than becoming embedded features of school life. SHINE worked through a network of CSO partners to establish more than 500 clubs in five countries. While it was active, our partners provided direct support, guidance, and encouragement to schools and club members. When this support ended, the clubs slowly fade away.

What we’re learning about sustainability

This finding reminds us that sustainability isn't simple. In a previous publication, we outlined our framework for thinking about what it means to deliver lasting change. This framework spans four levels, from continuation of project activities through to internalisation of underlying principles, maintaining of outcomes, and persistent shifts in social systems and norms.

When SHINE clubs stopped meeting, project-level sustainability clearly failed. But what about the other dimensions?

The personal transformations that supported teenagers underwent — assertiveness, problem-solving, relationship-building, responsibility, the vital experience of being heard — have these become a lasting part of who they are? Tracking former school students would go beyond what we are in a position to do, but some memories must remain. An official from Kenya's Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) described Integrity Clubs as "incubators of ethical leadership," helping members to develop values and behaviours that extend beyond school life.

Likewise, improved infrastructure will continue to serve new students into the future. Buildings don't disappear when school projects end.

What's less clear is whether the broader shifts in school culture that we observed can be sustained without active clubs to maintain them. This is what we're still learning: which types of outcomes can we reasonably expect to last (almost) by themselves, and which require ongoing structures and investment?

The missing piece: Local ownership

Our previous sustainability research divided success factors into four groups: having the right timeframes, motivations, funding, and partnerships. This evaluation focused on the latter two, highlighting that what is essential for sustaining Integrity Clubs is genuine ownership and buy-in from school management and education authorities.

We have evidence that Integrity Clubs create remarkable impact, not only for students but for entire educational environments. What they need to survive is to be seen as integral to what schools do, not as external additions dependent on NGO support.

This means school management committees budgeting for Integrity Clubs as core extracurricular activities. It means engaging all teachers across the school, not just one appointed patron. It means Boards of Management and parents being actively informed about what clubs are achieving. It means the Ministry of Education and EACC coordinating more effectively, and providing sufficient resources rather than having one EACC official to cover three counties. In future, it may mean sharing success stories through platforms like the Kenya Secondary Schools Heads Association.

What happens now

Our new evaluation has reinforced the evidence for what Integrity Clubs deliver, for students and for their school communities. The nature of some of these outcomes means that they will likely endure, or at least linger, but other aspects appear fragile without sustained structures to maintain them.

What we're increasingly certain about is that making Integrity Clubs into long-living structures requires moving the perception of them from ‘external projects’ to embedded practices, with local resourcing and ownership to match. In our current programme, we're looking at immediate steps to encourage this: support individual schools with tailored sustainability plans, and broadening teacher engagement beyond club patrons.

This isn't just about Integrity Clubs. It's about how we think about our impact more broadly, and recognising that different levels of change require different types of support to endure. Being honest about what we know, what we hope for, and what we still need to learn will help us to design better programmes and to deliver change that won’t fade once we’re gone.

This evaluation was conducted by a team from Owl RE, led by Obando Ekesa. Read the report in full here, where you can also find a summary of findings.

The five sampled SHINE schools were selected from the 45 supported by Kesho Kenya in Kilifi North Sub-County from 2017-21. The ten new clubs are located in Magarini Sub-County, which has been historically under-served by development actors. Integrity Action has a how-to guide to Integrity Clubs, developed with input from students in Kenya, Palestine, and Nepal.

To share your thoughts on any of the issues discussed in this blog, contact daniel.burwood@integrityaction.org