“Before they burnt the dormitories. Now they use the communication channels.”

Integrity Clubs, in which school students monitor the education services they receive, aim to make education more accountable and responsive. But in Kenya, we found that they were also reducing conflict

Fires in secondary schools, started by students as an act of protest, are not unusual in Kenya. One researcher tracked at least 750 arson attempts at Kenyan secondary boarding schools from 2008-18. There were 25 cases in January 2021 alone, after schools returned from the COVID-19 lockdown. And there are many other examples of unrest including riots.

This is why we were particularly interested to hear this reflection from Duncan Orina, Deputy Principal and Patron of Lutsangani Secondary School in Kilifi county, Kenya: “Before, they burnt the dormitories to address an issue. Nowadays they use the communication channels and are welcome to approach the teachers and management.”

Lutsangani Secondary was one of 110 Kenyan secondary schools that took part in the SHINE programme, run by Integrity Action and various partner organisations in five countries (Kenya, DR Congo, Palestine, Nepal, Afghanistan).

The SHINE programme established Integrity Clubs in secondary schools. These clubs involved students aged 15-18 and focussed on promoting integrity in the school, particularly by monitoring key aspects of education delivery. Clubs looked at teacher absenteeism, quality of new and existing infrastructure, water and sanitation provision, accessibility for students with disabilities, and many other issues. Based on the monitoring, club members identified problems and worked collaboratively with school management to find solutions.

The SHINE programme aimed to – and succeeded in – bringing about many positive changes to how education services were delivered, as detailed in a recent independent evaluation. But in Kenya, alongside these results, Integrity Action’s partner organisation Kesho Kenya heard from teachers, headteachers and students at multiple schools about how Integrity Clubs had reduced unrest and conflict.

For example John Muasya, Deputy Principal of Chumani Secondary School, said, “At least once a term, we had unrest. Then students break everything, and parents need to pay for the repair of infrastructure but often don’t have the money. Last year we did not have any strike.”

What is happening here? It is useful to explore exactly why unrest has been happening in Kenyan schools. Some have characterised it as little more than a lack of discipline – most notably the Education Cabinet Secretary – to which the solution is simply stricter rules and more punishment. But multiple pieces of research suggest that this doesn’t get close to the root cause.

Masonga and Makahamadze (2020) found that “student violence was a response to the devaluing and oppressive environment in boarding schools”. Cooper (2014) highlighted “students' recognition that destructive collective actions are efficacious in winning a response from the authorities.” In a more recent article, Cooper relayed a vivid quote from a student: “At first you start with the suggestion box. And if they refuse to reply, you go to another tactic like a riot. And if that doesn’t work, then a fire. And then they’ll come to agree with us that they must do something.”

To respond to these issues, Masonga and Makahamadze argued that “school authorities could mitigate violent protests by providing formal political means of representation and democratic decision-making; creating new spaces for negotiation and peaceful protest; listening to the voices of students; and engaging in dialogue to create a common vision and mission.” We believe that’s what Integrity Clubs have contributed to.

Take this reflection from an Integrity Club member at Bahari Girls’ School in Kilifi county: “We used to fear teachers a lot and did not know how to approach them if we had grievances or issues concerning us, this meant that sometimes we would be rebellious and cause commotions in school which sometimes meant that we would be sent home. When the SHINE project came, we learnt how to create an environment for dialogue and to solve problems while at school. We also learnt how to approach the principal and share our concerns and since then we have not seen the need to cause chaos in the school because we feel the school is listening.”

So how does all this relate to accountability, and the promotion of accountable education services? As recounted above, the reduction in unrest allowed students and staff to discuss the problems they were facing more constructively. At Chumani secondary school, students had been unhappy with the failure of a caterer to deliver bread for the students’ breakfasts each morning; students and staff then hit upon the idea of establishing a bakery in a spare room at the school. This allowed the school to meet its commitment of feeding the boarding students each morning and save money.

The potential for collaboration between citizens and duty-bearers is an important part of Integrity Action’s theory of change, wherein one of the underlying preconditions is that “constructive collaboration is possible”. We have witnessed how demands for integrity and accountability often involve negotiation and relationship-building, rather than a simple “demand and response”. Meanwhile the final report from the Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA) programme highlighted “building trust between people and public authorities” as a key stepping stone towards accountable governance, and our research on problem-solving in service delivery also highlighted the importance of mutual trust, and subsequent collaboration, in reaching solutions.

There is another interesting link to accountability. During the SHINE programme, Integrity Clubs chose various different issues to focus on, like the quality of facilities and presence of teachers. What we often saw was that Integrity Clubs also chose to focus on – and effectively “monitor” – student behaviour. From a rights-based perspective, where citizens have rights and duty-bearers have duties, this might seem a little uncomfortable. Should students have the “duty” to behave? (And what is “good behaviour” anyway? And who decides? Important questions I don’t have space to explore here!)

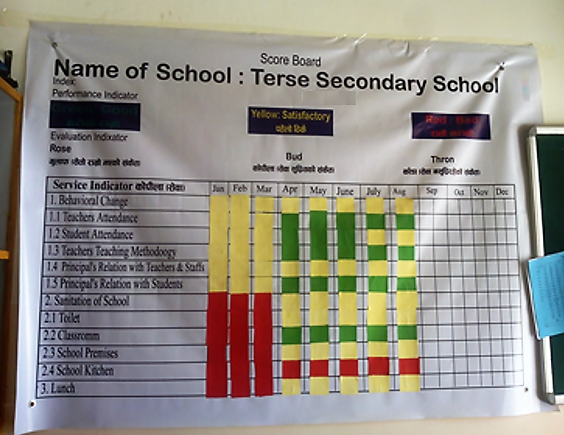

Scorecard from a school in the SHINE programme tracking how their school is performing over time

However it makes more sense if we think of this as a social contract, where citizens have certain “responsibilities” in return for having their rights realised, like paying taxes and obeying the law. As part of the effort to promote accountability and integrity in schools, it seemed that students were finding it useful to hold themselves accountable too – and without this, it may have been harder for students to demand greater accountability from teachers, who (let’s face it) are far more powerful in this context.

This issue of citizens having responsibilities came up in our research on “what makes duty-bearers act with integrity”. It found that “from the teachers’ perspective, when students are motivated to learn, this makes teachers more motivated to perform their role with integrity.” It also came up in the ACT Health programme and research in Uganda, which used a “3Rs” framework to approach accountability: responsibility, responsiveness, and relationships. The research found that this framing “created a safe starting point for citizens to engage power-holders.”

Having seen what this kind of collaborative approach can achieve in schools, we are keen to find ways to spread it. To help with this we have produced an Integrity Clubs how-to guide, in collaboration with some of the students who took part in the SHINE programme. We also produced an earlier guidebook. Please do contact us if you’d like to engage on this – we are always happy to connect.

Header photo: Students and teachers engaging as part of the SHINE programme to find solutions for problems identified in their school